I’ve always been fascinated by history, especially human history, and Scotland, according to a quick internet search, has been inhabited for around 14,000 years. That history is everywhere, and I mean everywhere. I’d bet that if you put a shovel in the ground anywhere here and dug deep enough, you’d find evidence of human activity. On this extended visit, we wanted to do more than just visit castles and historic sites, and that’s when we discovered the website “Dig It Scotland.”

Port Castle

Unsure of what to expect, we initially signed up to volunteer for a single day on a week-long dig at Port Castle, a fortified site that had never previously been excavated. It was believed to be a fort dating back to the Iron Ages, after the Romans had left Britain, with later reuse in medieval times as the early Scottish kingdoms took shape.

The site is located on a rocky promontory near St. Ninian’s Cave overlooking the Irish Sea on the Solway Coast in the south of Scotland. The remains of the fort are bounded by ruinous low walls following the edge of the promontory, and the defensive position is strengthened by a further wall on the north, providing additional protection from land approaches. The area is now overgrown with mounds of grass and other vegetation, which have accumulated over the years. The aim of the dig was to open three trenches to try and determine the scale and interconnections of the fort walls and to see if there was evidence of multiple uses over time.

We were going to be working, along with several other volunteers, under the watchful eye of experts Graeme and Dominic from AOC Archaeology Group. After a quick crash course in what was required, we were assigned to an open trench along the outer fort wall, and off we went to start digging with our trowels, mattocks, and shovels. The archaeologists were looking for signs of a ditch or any change in the colour or texture of the soil that might show where a defensive ditch once existed, which would fit with the idea of an Iron Age site. However, after about an hour of digging with no sign of a ditch, the archaeologist called for a tea break; it is Scotland, after all!

We then moved to the inner section of the fort, with Keith and I working in different trenches. One was located on the inside of the outer wall and involved simply removing the spill (stones that had previously been part of the wall) to try and find the wall’s depth below the current ground level. The other trench was at the intersection of the internal wall with the outer wall. Here, a rough opening hinted at what may have been an entrance or passageway between inner chambers. Further excavation in this trench uncovered a fairly clear line of stones with a lintel stone also visible. With an absence of buried artifacts, this doorway was the main discovery of the day.

Once we were done for the day, the archaeologists reviewed what had been uncovered and led them to make an exciting declaration: they believed the site wasn’t an Iron Age fort at all but simply a defensive castle from the medieval period. The excavations showed no outer ditch, which would have been indicative of an Iron Age structure, and there was no change in the formation or style of the stone, suggesting it was all constructed and used during a single period. It will be interesting to find out if this hypothesis is confirmed after the soil samples and all other evidence have been reviewed.

For us, it was an engaging educational experience, and although it rained all afternoon and we got soaked and muddy, it was still fun and something we looked forward to doing again.

Stroanfreggan Fort and Kerbed Cairn

After our experience at the Port Castle dig, we were hooked, so when we spotted another local opportunity on the Dig It! website, we didn’t hesitate. This time, we signed up for three days over a four-week excavation at Stroanfreggan Craig, tucked into the rolling hills of the Dumfries and Galloway countryside.

At this site, there is a Kerb Cairn, which has been reduced to a low grassy circular platform at the base of the crag, and remnants of an Iron Age hill fort on a rocky ridge, which is where we would be excavating.

We joined the team in opening a new trench, starting with the deturfing and careful removal of the topsoil before trowelling down layer by layer. Our goal was to reach the base of the fort wall, and by the end, we hit bedrock, confirming we’d reached it. Along the way, we learned how to photograph and record the archaeology properly, capturing every stage of the process.

Returning for multiple days allowed us to become more immersed in unearthing the fort structure and gave us a chance to learn new techniques, including the process for photographing and recording observations at different stages of the project. And we got to sample the ever-changing Scottish weather.

Although we didn’t uncover any artifacts, the lead archaeologist reminded us that’s not unusual for an Iron Age site. These digs are often more about understanding structure and landscape than unearthing treasures. Still, there was something deeply satisfying about standing there, covered in Scottish mud, knowing we’d helped reveal another small piece of Scotland’s ancient past.

This project was initiated by a local historical organization and was promoted to include local schools and open days for the public. There was even a write-up in Scotland’s main national daily newspaper!

Birgham Cemetery Survey

While we were digging and excavating at Stroanfreggan, we got to chat with the professional archaeologists, Cathy and Leona, working alongside us. They told us about a new three-year history project called “Uncovering the Tweed,” which had just received funding, and shared how we could get involved. As you can probably tell by now, we were loving the chance to volunteer, learn new skills, and dive into different slices of history, so we signed up for our next adventure, surveying a cemetery in the Scottish Borders.

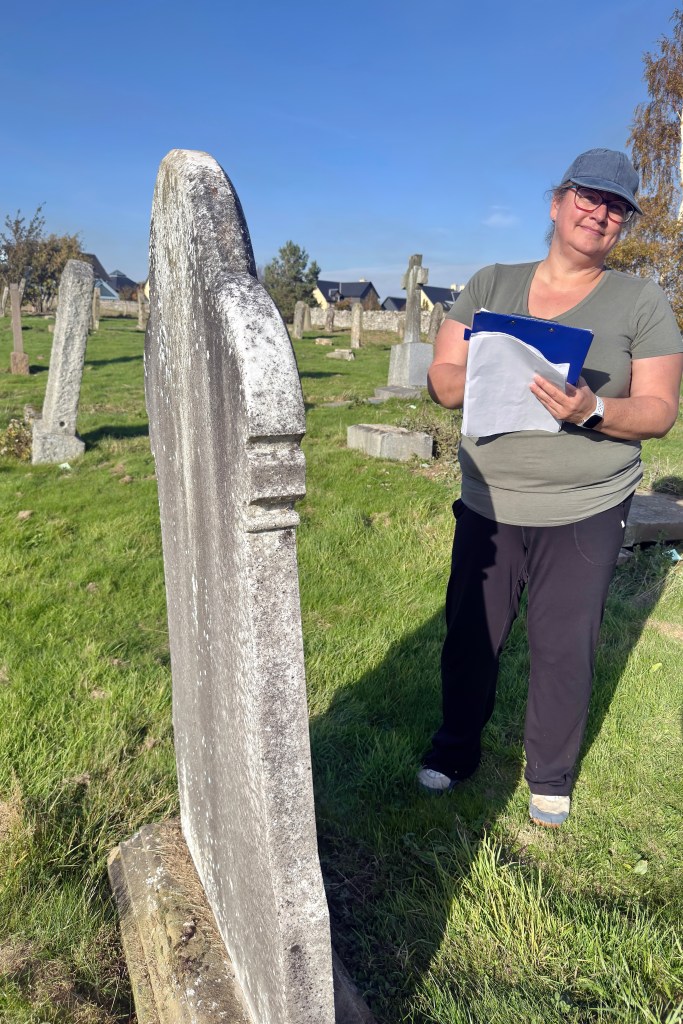

Birgham is a village located on the banks of the River Tweed, near the English border in the southeast of Scotland. The survey was intended to record the historic gravestones and grave slabs that survive within this historic cemetery, some of which date back to the 1700s.

Upon arrival at the cemetery, we learned about the Mytum form, a standardized coding document for systematically recording the archaeological and historical details of memorial monuments in cemeteries and burial grounds.

For the next two days, each headstone was carefully numbered, GPS-located, and photographed. The Mytum form was used to systematically record all the details, including the material, shape, condition, and the direction the headstone is facing. As well as the inscription and year of erection, this method even documents the headstone font. There are also codes for decorative elements such as columns and motifs such as flowers, crowns, and even horses. It is quite comprehensive!

The idea is to treat each memorial as a piece in a larger cultural puzzle, so by recording everything in the same structured manner, you can compare sites, find patterns between locations of the same age, and preserve information before it’s lost.

The GPS survey data precisely mapped the location of each burial site, and drone footage recorded the overall site plan and topographical features. Old records indicate that there was once a chapel on this site, and hopefully the newly recorded data will uncover a clear indication of where it stood.

The experience of methodically walking the cemetery rows, numbering stones, taking GPS readings, photographing every angle, and filling in the forms made us feel part of something meaningful. We were helping to record history, the silent stories of people buried long ago, and in doing so, we were gaining new archaeological skills and a deeper respect for how much a headstone can tell us about a community’s change over time.

We will definitely be looking to continue our archeological adventures on future visits to Scotland!

Leave a comment